Today marks a Premiere on this wee blog, as that the following post is the first Guest Article on this site. I'm a huge fan and supporter of Devin Montgomery, the inventor of the first ultralight backcountry chimney kettle aka "The Backcountry Boiler". It is a fantastic project, and Devin will now set out and take you on a journey, talking about the origin of the Backcountry Boiler, the power of Making-Your-Own-Gear, Community Supported Development and ultralight backpacking.

Me hanging out with the Backcountry Boiler on a recent hike.

Origins

The story of the Backcountry Boiler really started in spring 2007. I had just returned from a 128-mile solo row down the entire length of the Monongahela River in southwestern Pennsylvania. Having enjoyed the trip so much, I looked for other ways to spend long days in the outdoors covering a great deal of distance (I was able to make about 20-25 miles per day in the boat). So I naturally turned to backpacking, but remembering the grueling slogs of a heavy pack when I was in Boy Scouts, I looked for a lighter way and came across ultralight backpacking.

In researching the field, I found that the "sacrifices" one had to make - no tent, a minimal sleeping pad, no spare clothes, a simple diet - meant little to me. What did strike me were the benefits - I could cover miles and miles in the beautiful outdoors, feeling more like I was simply taking a pleasant walk than hauling a load from point A to B.

So I took to my gear with scrutiny. One thing that had to go: my heavy MSR Whisperlite stove. Predictably, I turned to alcohol stoves and made my own out of a soda can. It was in researching designs for my stove that I first came across chimney kettles - the Kelly, the Thermette, a slew of others.

They were awesome. An ingenious design that uses almost any available fuel, aspirates combustion through something called the stack effect created by warm air flowing up through the chimney and pulling in new air through the inlet, creates a large surface area for heat transfer, and shields the fire from the wind. Oh, and heck, it could even be used as a canteen to carry water when not in use. Apparently, the perfect wood stove, really the perfect backpacking stove for those who eat a simple ultralight diet, and multi-purpose to boot!

The anatomy of a Chimney Kettle

Existing Products

The problem: the only ones available commercially were dinosaurs. They were ancient - no meaningful design changes had been made in over half a century - and they were big and heavy - the smallest and lightest one commercially available weighed 19 oz and took up around 250 ci of pack space. That's the weight I had budgeted for a three-season quilt, and even the fuel savings couldn't justify it.

I wasn't the only one who loved the idea of a chimney kettle but loathed the size and weight of those currently available. It's my understanding that Backpacking Light's Ryan Jordan even approached one of the existing manufacturers about a lighter version for his Arctic 1000 (before he worked with Bush Buddy on the Ultra), but that it was a no-go. Many of the solutions looked to either exotic, expensive metals like titanium, or ultra-low capacities for the weight savings. Others (including my initial efforts) looked to the use of existing aluminum bottles or cans hacked up and stuck together with high-temperature epoxy. But ultimately, all of these seemed unappealing approaches, and I thought there was just a better, simpler way to make to make a high-quality, smaller, lighter, but still very useful chimney kettle.

Design

So in early 2008, I very literally went back to the drawing board, starting from scratch. With the aid of what was then a relatively new, free CAD program, Google Sketchup, I stripped down the concept of a chimney kettle to its core elements: fuel, air, water. The solution had to be light, small, simple, packable, and it had to boil a reasonable amount of water in a reasonable amount of time. What I came up with had no extraneous parts or details, used simple geometric rules to minimize the amount of material needed for a given volume, and carefully balanced the interior space of the device between that allocated for combustion and that for water. Some of the aspects ended up mirroring existing products, some ended up being entirely new. The finished product was unlike anything else available.

A virtual Backcountry Boiler in the free software in which it was created.

I mocked it up out of aluminum of a thickness I considered durable enough for regular use and I came up with something remarkable: a chimney kettle that weighed 1/3 as much (under 6 oz vs. 19 oz), took up only a bit over 1/3 as much pack space (about 90 ci vs 250 ci) and boiled the same amount of water (20 oz) as the smallest, lightest other chimney kettle available! The only sacrifice was a slight increase in the amount of time it took to boil 2 cups of water. Against quotes of just 3 minutes for 2 cups with the existing product, mine took around 5 because of my intentional shrinking of the combustion chamber. A good compromise given all the benefits, I thought. Now I just had to get it made.

Seeking Manufacturing

As I discovered through my research, if you're looking to have thin-walled, deep aluminum parts made that have relatively low tooling costs and per-piece costs that diminish with scale, you have two options: metal spinning and hydro-forming. So armed with my design, I approached a number of metal spinning and hydro-forming shops around the U.S. But I was unfortunately met with bad news: none of them would provide me a quote to make the Boilers as light as I had designed them to be. The best I could get was something that was around 13-14 oz, and material thicknesses more than twice what I had determined would be mechanically sufficient through my mock-up. This was still 2008, and I was unimpressed enough with such a marginal improvement that I kept on pushing for a better solution.

Back to MYOG

Fortunately, through all of this research, I also came across more information on how metal spinning is performed. Specifically, I came across a PDF from a guy at Stanford that laid out the basics of metal spinning. Even better, I found some DVDs I could rent online, incidentally made by a guy only a few hours away from where I live, that showed how someone could make their own tools and basic parts on a wood lathe. So I rented the DVDs. Bought a lathe, grinder, drill press and some odds and ends from Harbor Freight (a discount tool supplier here in the states) for cheap. Made my own metal spinning tools. Learned how to turn wood for the forms, and tried to spin my parts.

But the first lathe was junk, so I got a second. The second lathe was much better (actually quite good for a wood lathe), but the parts I was making were larger and more difficult than those I had seen being made, and I needed a proper metal spinning lathe. I found an antique in Arizona, not too far from where one of my sisters lives, and had her (with much appreciation) freight ship it to me. I had some work done on it, wired up a motor to run it, and in June 2009, popped off the first living, breathing Boiler (though it didn't have the name at the time). I've taken that prototype on every hike since and it has performed marvelously.

The evolution of the Backcountry Boiler pre-production.

Community Supported Development

All this time, and in true MYOG fashion, I was sharing my progress with the online community at Backpacking Light. I had come to the site in an effort to lighten my load, but came to find a great deal more. Ultralight backpacking is, in my mind and the minds of many, about a lot more than ounces and grams. It's about being analytical about how we experience the outdoors. When that way of thinking is applied to gear, it only makes sense that it should be light. You do have to carry it after all, and each comfort in camp at night has to earn its passage on you back during the day.

It is because of this analytical approach that Backpacking Light has what I would say is one of the most, if not the most, thriving MYOG communities anywhere. My project and I fit nicely into that community. The gratuitous support I received there is what kept me going on this project despite novice skill, never having a proper workshop, and developing it over the same three years as I happened to be in both law and business schools - two very rigorous programs.

It is there that I first made more of the Boiler (it had acquire the nickname "Montgomery Kettle," which I happily went with for some time) available to others for reservations in spring of 2010. At the time, I had an open summer ahead of me, and I was optimistic about turning out a bunch for my online compatriots. Fortunately for me, but unfortunately for the Boiler, I was then presented with the opportunity for some work on a very exciting, but not related to the outdoors, project I couldn't pass up. I continued work on the Boiler in the time I did have, but perhaps unsurprisingly, found it extremely difficult to mass produce a cutting edge product on my back porch in my spare time.

The entirety of the workshop where the Backcountry Boiler was prototyped.

When school started up again in the fall, I had no real choice but to put the project in the back seat until I graduated in the winter. In the middle of that last hectic semester, the Backpacking Light community found out that one person who had been posing as a customer and seeking a lot of specific details about the Boiler was now shopping around a copy he paid to have made.

Aside from what I've already said, the only thing I really have to say about that is that developing a product in the open has both benefits and costs. There have been scores of people who have found my project interesting and have offered support. One guy found it interesting and decided that he would rather be the one benefitting from it. I wouldn't take away the experience of the former to avoid the exploitation of the latter. I think people still value authenticity in the goods they buy, and I have gotten a lot of support that confirms that belief.

Local, Community Funded Manufacturing

Given that it looked like the world wouldn't wait for me to finish school, and that I certainly didn't have the time to make them all myself in the middle of the semester, I again approached a local spinning shop about having them make the Boiler. Better news came this time and the difference was that I knew what I wanted to have made was possible. I was able to show them my prototype and walk them through the process I used. Having them replicate my efforts took longer than expected, but that speaks to the great things one devoted person can accomplish. Their persistence in following though with the difficult task speaks to the value of creating personal relationships with suppliers, and how local manufacturing lends itself to those kinds of relationships. The production Boiler weighs just a bit more and has just a bit less volume than my prototypes, but the manufacturing is a lot more reliable.

A crew member of a local spinning shop working on the production version of the Boiler.

Now that I could have them made by a commercial shop, I again turned to the community for support. Because I've done this whole project while being a student and living on loans, it has always been done on a shoestring budget. The largest single capital investment that it has required, for instance, was the antique lathe I used for prototyping. In what may have been one of the most effective uses of government dollars, I paid for the lathe with an economic stimulus tax rebate issued by the US government in 2008.

But to pay for a large enough run for the Boilers to be affordable, I was going to have to order quite a large quantity - requiring more capital than I could fork out myself. So I opened up pre-orders to pay for production and response was excellent. I sold over 100 in a week, thanks in large part to efforts of friends of the project who spread the word about it on a slew of forums and blogs. As a thank you to supporters, I offered them at cost, but accepted tips of 10, 20 or 30%. More than half of those who ordered paid more than they had to out of sheer goodwill towards the project. In business lingo, this method of financing is called "crowd funding" and is a powerful tool being used to fund creative projects all over.

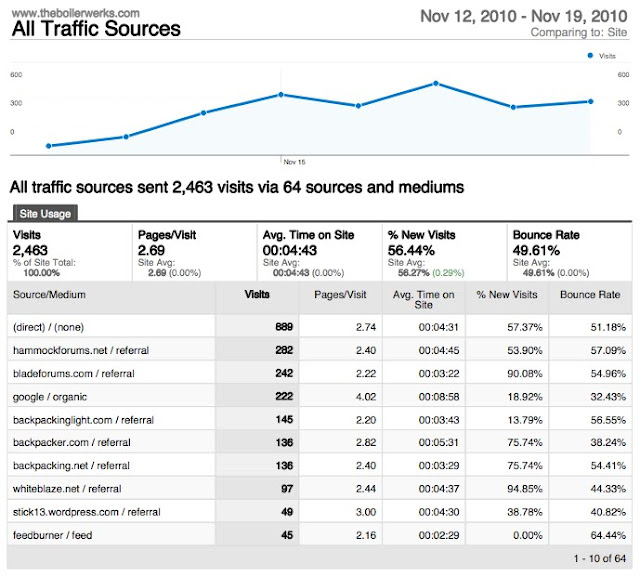

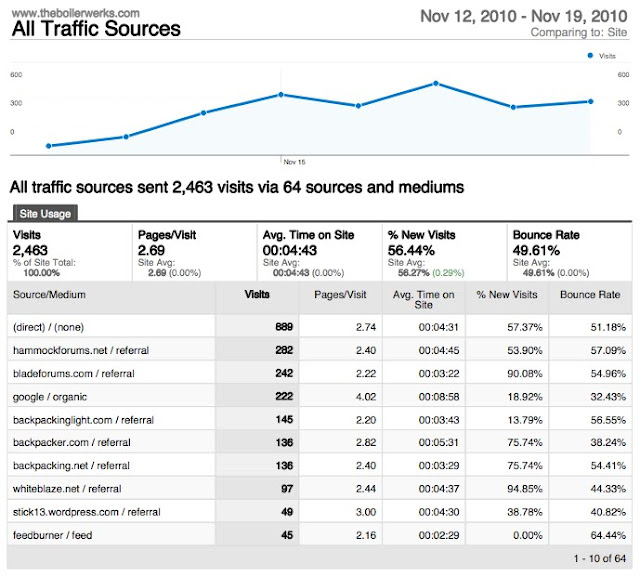

Google analytics report for the week pre-orders were open. Note the significant traffic from referring sites, all of which was generated by unsolicited postings by supporters of the project.

The Takeaway

What I take from this experience, what I think is even more interesting than the development of a single product, is that the playing field in outdoor product development is more level than one might think. The Backcountry Boiler lightened and shrunk the state-of-the-art in chimney kettles by about a third, with no significant decrease in capacity or performance. That level of improvement is almost unheard of, and, in my humble estimation, presents a product that has an appeal entirely new from anything that came before it. The route I have taken isn't that heavy in investment capital, but demands a lot in terms of creativity, persistence, and community engagement. But I think it's better for it. This product is just one example of how this recipe can realize innovations in a field that has been fallow for decades. And it's this kind of development to which I would look for the next bit of exciting gear.

The other thing I take away is how very powerful the online communities we build are. The Boiler simply wouldn’t have come about if it weren’t for these communities. They pull in people from all over the world, based around common interests rather than geographic location. They support good ideas and can smell a phony. All I’ve done is be myself and treat those I interact with like real people and I’ve gained a lot as a result.

The Backcountry Boiler: endless hot water anywhere all for about the same size and weight as a wide-mouthed water bottle.

What's Next

Backcountry Boiler as a product and my blog, The Boilerwerks, as a documentation project are here to stay. I'm still trying to figure out a name to incorporate under. The pre-ordered Boilers will be shipped out in a few weeks, and in the same batch are a number that will be available through Backpacking Light (just announced today!). But I'm already planning the next large group buy, which will allow more people to be involved in building this project and should provide some of the capital for me to start keeping an inventory.

There are already two improvements on the Boiler that I'm working on, but that won't be ready in time for the initial shipment. They will, however, be entirely backward compatible with the current Boilers. I don't really believe in planned obsolescence. There is at least one accessory for the Boiler that I plan on thoroughly involving the community in developing. Beyond that, I'm excited about some other concepts in stove design that I've been working on, but they're on hold until the Boiler is properly established. What I can say is that they will use fuels that I believe have been under-utilized, namely not the ubiquitous alcohol.

But again, even more than manufacturing specific products, I'm really interested in exploring the whole process of making and making available innovative outdoor gear. Personally, I want to become more proficient in the use of design software, and learn to work with some new materials. I want to continue engaging the outdoor community in what I do and see what great things we are capable of.

---

Many, many thanks to Devin for this great article! I enjoyed it a lot, and look now even more forward to receiving my Backcountry Boiler!

Me hanging out with the Backcountry Boiler on a recent hike.

Origins

The story of the Backcountry Boiler really started in spring 2007. I had just returned from a 128-mile solo row down the entire length of the Monongahela River in southwestern Pennsylvania. Having enjoyed the trip so much, I looked for other ways to spend long days in the outdoors covering a great deal of distance (I was able to make about 20-25 miles per day in the boat). So I naturally turned to backpacking, but remembering the grueling slogs of a heavy pack when I was in Boy Scouts, I looked for a lighter way and came across ultralight backpacking.

In researching the field, I found that the "sacrifices" one had to make - no tent, a minimal sleeping pad, no spare clothes, a simple diet - meant little to me. What did strike me were the benefits - I could cover miles and miles in the beautiful outdoors, feeling more like I was simply taking a pleasant walk than hauling a load from point A to B.

So I took to my gear with scrutiny. One thing that had to go: my heavy MSR Whisperlite stove. Predictably, I turned to alcohol stoves and made my own out of a soda can. It was in researching designs for my stove that I first came across chimney kettles - the Kelly, the Thermette, a slew of others.

They were awesome. An ingenious design that uses almost any available fuel, aspirates combustion through something called the stack effect created by warm air flowing up through the chimney and pulling in new air through the inlet, creates a large surface area for heat transfer, and shields the fire from the wind. Oh, and heck, it could even be used as a canteen to carry water when not in use. Apparently, the perfect wood stove, really the perfect backpacking stove for those who eat a simple ultralight diet, and multi-purpose to boot!

The anatomy of a Chimney Kettle

Existing Products

The problem: the only ones available commercially were dinosaurs. They were ancient - no meaningful design changes had been made in over half a century - and they were big and heavy - the smallest and lightest one commercially available weighed 19 oz and took up around 250 ci of pack space. That's the weight I had budgeted for a three-season quilt, and even the fuel savings couldn't justify it.

I wasn't the only one who loved the idea of a chimney kettle but loathed the size and weight of those currently available. It's my understanding that Backpacking Light's Ryan Jordan even approached one of the existing manufacturers about a lighter version for his Arctic 1000 (before he worked with Bush Buddy on the Ultra), but that it was a no-go. Many of the solutions looked to either exotic, expensive metals like titanium, or ultra-low capacities for the weight savings. Others (including my initial efforts) looked to the use of existing aluminum bottles or cans hacked up and stuck together with high-temperature epoxy. But ultimately, all of these seemed unappealing approaches, and I thought there was just a better, simpler way to make to make a high-quality, smaller, lighter, but still very useful chimney kettle.

Design

So in early 2008, I very literally went back to the drawing board, starting from scratch. With the aid of what was then a relatively new, free CAD program, Google Sketchup, I stripped down the concept of a chimney kettle to its core elements: fuel, air, water. The solution had to be light, small, simple, packable, and it had to boil a reasonable amount of water in a reasonable amount of time. What I came up with had no extraneous parts or details, used simple geometric rules to minimize the amount of material needed for a given volume, and carefully balanced the interior space of the device between that allocated for combustion and that for water. Some of the aspects ended up mirroring existing products, some ended up being entirely new. The finished product was unlike anything else available.

A virtual Backcountry Boiler in the free software in which it was created.

I mocked it up out of aluminum of a thickness I considered durable enough for regular use and I came up with something remarkable: a chimney kettle that weighed 1/3 as much (under 6 oz vs. 19 oz), took up only a bit over 1/3 as much pack space (about 90 ci vs 250 ci) and boiled the same amount of water (20 oz) as the smallest, lightest other chimney kettle available! The only sacrifice was a slight increase in the amount of time it took to boil 2 cups of water. Against quotes of just 3 minutes for 2 cups with the existing product, mine took around 5 because of my intentional shrinking of the combustion chamber. A good compromise given all the benefits, I thought. Now I just had to get it made.

Seeking Manufacturing

As I discovered through my research, if you're looking to have thin-walled, deep aluminum parts made that have relatively low tooling costs and per-piece costs that diminish with scale, you have two options: metal spinning and hydro-forming. So armed with my design, I approached a number of metal spinning and hydro-forming shops around the U.S. But I was unfortunately met with bad news: none of them would provide me a quote to make the Boilers as light as I had designed them to be. The best I could get was something that was around 13-14 oz, and material thicknesses more than twice what I had determined would be mechanically sufficient through my mock-up. This was still 2008, and I was unimpressed enough with such a marginal improvement that I kept on pushing for a better solution.

Back to MYOG

Fortunately, through all of this research, I also came across more information on how metal spinning is performed. Specifically, I came across a PDF from a guy at Stanford that laid out the basics of metal spinning. Even better, I found some DVDs I could rent online, incidentally made by a guy only a few hours away from where I live, that showed how someone could make their own tools and basic parts on a wood lathe. So I rented the DVDs. Bought a lathe, grinder, drill press and some odds and ends from Harbor Freight (a discount tool supplier here in the states) for cheap. Made my own metal spinning tools. Learned how to turn wood for the forms, and tried to spin my parts.

But the first lathe was junk, so I got a second. The second lathe was much better (actually quite good for a wood lathe), but the parts I was making were larger and more difficult than those I had seen being made, and I needed a proper metal spinning lathe. I found an antique in Arizona, not too far from where one of my sisters lives, and had her (with much appreciation) freight ship it to me. I had some work done on it, wired up a motor to run it, and in June 2009, popped off the first living, breathing Boiler (though it didn't have the name at the time). I've taken that prototype on every hike since and it has performed marvelously.

The evolution of the Backcountry Boiler pre-production.

Community Supported Development

All this time, and in true MYOG fashion, I was sharing my progress with the online community at Backpacking Light. I had come to the site in an effort to lighten my load, but came to find a great deal more. Ultralight backpacking is, in my mind and the minds of many, about a lot more than ounces and grams. It's about being analytical about how we experience the outdoors. When that way of thinking is applied to gear, it only makes sense that it should be light. You do have to carry it after all, and each comfort in camp at night has to earn its passage on you back during the day.

It is because of this analytical approach that Backpacking Light has what I would say is one of the most, if not the most, thriving MYOG communities anywhere. My project and I fit nicely into that community. The gratuitous support I received there is what kept me going on this project despite novice skill, never having a proper workshop, and developing it over the same three years as I happened to be in both law and business schools - two very rigorous programs.

It is there that I first made more of the Boiler (it had acquire the nickname "Montgomery Kettle," which I happily went with for some time) available to others for reservations in spring of 2010. At the time, I had an open summer ahead of me, and I was optimistic about turning out a bunch for my online compatriots. Fortunately for me, but unfortunately for the Boiler, I was then presented with the opportunity for some work on a very exciting, but not related to the outdoors, project I couldn't pass up. I continued work on the Boiler in the time I did have, but perhaps unsurprisingly, found it extremely difficult to mass produce a cutting edge product on my back porch in my spare time.

The entirety of the workshop where the Backcountry Boiler was prototyped.

When school started up again in the fall, I had no real choice but to put the project in the back seat until I graduated in the winter. In the middle of that last hectic semester, the Backpacking Light community found out that one person who had been posing as a customer and seeking a lot of specific details about the Boiler was now shopping around a copy he paid to have made.

Aside from what I've already said, the only thing I really have to say about that is that developing a product in the open has both benefits and costs. There have been scores of people who have found my project interesting and have offered support. One guy found it interesting and decided that he would rather be the one benefitting from it. I wouldn't take away the experience of the former to avoid the exploitation of the latter. I think people still value authenticity in the goods they buy, and I have gotten a lot of support that confirms that belief.

Local, Community Funded Manufacturing

Given that it looked like the world wouldn't wait for me to finish school, and that I certainly didn't have the time to make them all myself in the middle of the semester, I again approached a local spinning shop about having them make the Boiler. Better news came this time and the difference was that I knew what I wanted to have made was possible. I was able to show them my prototype and walk them through the process I used. Having them replicate my efforts took longer than expected, but that speaks to the great things one devoted person can accomplish. Their persistence in following though with the difficult task speaks to the value of creating personal relationships with suppliers, and how local manufacturing lends itself to those kinds of relationships. The production Boiler weighs just a bit more and has just a bit less volume than my prototypes, but the manufacturing is a lot more reliable.

A crew member of a local spinning shop working on the production version of the Boiler.

Now that I could have them made by a commercial shop, I again turned to the community for support. Because I've done this whole project while being a student and living on loans, it has always been done on a shoestring budget. The largest single capital investment that it has required, for instance, was the antique lathe I used for prototyping. In what may have been one of the most effective uses of government dollars, I paid for the lathe with an economic stimulus tax rebate issued by the US government in 2008.

But to pay for a large enough run for the Boilers to be affordable, I was going to have to order quite a large quantity - requiring more capital than I could fork out myself. So I opened up pre-orders to pay for production and response was excellent. I sold over 100 in a week, thanks in large part to efforts of friends of the project who spread the word about it on a slew of forums and blogs. As a thank you to supporters, I offered them at cost, but accepted tips of 10, 20 or 30%. More than half of those who ordered paid more than they had to out of sheer goodwill towards the project. In business lingo, this method of financing is called "crowd funding" and is a powerful tool being used to fund creative projects all over.

Google analytics report for the week pre-orders were open. Note the significant traffic from referring sites, all of which was generated by unsolicited postings by supporters of the project.

The Takeaway

What I take from this experience, what I think is even more interesting than the development of a single product, is that the playing field in outdoor product development is more level than one might think. The Backcountry Boiler lightened and shrunk the state-of-the-art in chimney kettles by about a third, with no significant decrease in capacity or performance. That level of improvement is almost unheard of, and, in my humble estimation, presents a product that has an appeal entirely new from anything that came before it. The route I have taken isn't that heavy in investment capital, but demands a lot in terms of creativity, persistence, and community engagement. But I think it's better for it. This product is just one example of how this recipe can realize innovations in a field that has been fallow for decades. And it's this kind of development to which I would look for the next bit of exciting gear.

The other thing I take away is how very powerful the online communities we build are. The Boiler simply wouldn’t have come about if it weren’t for these communities. They pull in people from all over the world, based around common interests rather than geographic location. They support good ideas and can smell a phony. All I’ve done is be myself and treat those I interact with like real people and I’ve gained a lot as a result.

The Backcountry Boiler: endless hot water anywhere all for about the same size and weight as a wide-mouthed water bottle.

What's Next

Backcountry Boiler as a product and my blog, The Boilerwerks, as a documentation project are here to stay. I'm still trying to figure out a name to incorporate under. The pre-ordered Boilers will be shipped out in a few weeks, and in the same batch are a number that will be available through Backpacking Light (just announced today!). But I'm already planning the next large group buy, which will allow more people to be involved in building this project and should provide some of the capital for me to start keeping an inventory.

There are already two improvements on the Boiler that I'm working on, but that won't be ready in time for the initial shipment. They will, however, be entirely backward compatible with the current Boilers. I don't really believe in planned obsolescence. There is at least one accessory for the Boiler that I plan on thoroughly involving the community in developing. Beyond that, I'm excited about some other concepts in stove design that I've been working on, but they're on hold until the Boiler is properly established. What I can say is that they will use fuels that I believe have been under-utilized, namely not the ubiquitous alcohol.

But again, even more than manufacturing specific products, I'm really interested in exploring the whole process of making and making available innovative outdoor gear. Personally, I want to become more proficient in the use of design software, and learn to work with some new materials. I want to continue engaging the outdoor community in what I do and see what great things we are capable of.

---

Many, many thanks to Devin for this great article! I enjoyed it a lot, and look now even more forward to receiving my Backcountry Boiler!